As we know from the chapter Data types, there are eight data types in JavaScript. Seven of them are called “primitive”, because their values contain only a single thing (be it a string or a number or whatever).

In contrast, objects are used to store keyed collections of various data and more complex entities. In JavaScript, objects penetrate almost every aspect of the language. So we must understand them first before going in-depth anywhere else.

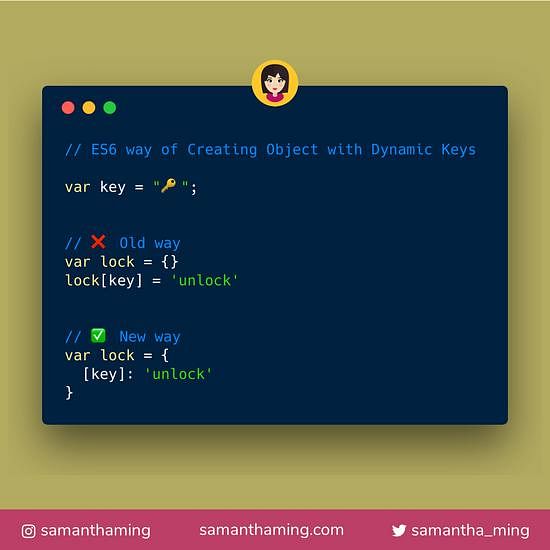

#How to Set Dynamic Property Keys with ES6 🎉 Previously, we had to do 2 steps - create the object literal and then use the bracket notation. With ES6, you can now directly use a variable as your property key in your object literal. Objects are the strong pillars of JavaScript. As a fact, everything in JavaScript is an object and they all have got properties and methods on them. The properties are simply the variables under the scope of that object and methods are the functions scoped under that object. The key are the names of the object's properties. Square brackets: jsObj'key' + i = 'example' + 1; In JavaScript, all arrays are objects, but not all objects are arrays. The primary difference (and one that's pretty hard to mimic with straight JavaScript and plain objects) is that array instances maintain the length property so that it reflects one plus the numeric value of the property whose name is numeric and whose value, when converted.

An object can be created with figure brackets {…} with an optional list of properties. A property is a “key: value” pair, where key is a string (also called a “property name”), and value can be anything.

We can imagine an object as a cabinet with signed files. Every piece of data is stored in its file by the key. It’s easy to find a file by its name or add/remove a file.

An empty object (“empty cabinet”) can be created using one of two syntaxes:

Usually, the figure brackets {...} are used. That declaration is called an object literal.

Literals and properties

We can immediately put some properties into {...} as “key: value” pairs:

A property has a key (also known as “name” or “identifier”) before the colon ':' and a value to the right of it.

In the user object, there are two properties:

- The first property has the name

'name'and the value'John'. - The second one has the name

'age'and the value30.

The resulting user object can be imagined as a cabinet with two signed files labeled “name” and “age”.

We can add, remove and read files from it any time.

Property values are accessible using the dot notation:

The value can be of any type. Let’s add a boolean one:

To remove a property, we can use delete operator:

We can also use multiword property names, but then they must be quoted:

The last property in the list may end with a comma:

That is called a “trailing” or “hanging” comma. Makes it easier to add/remove/move around properties, because all lines become alike.

Square brackets

For multiword properties, the dot access doesn’t work:

JavaScript doesn’t understand that. It thinks that we address user.likes, and then gives a syntax error when comes across unexpected birds.

The dot requires the key to be a valid variable identifier. That implies: contains no spaces, doesn’t start with a digit and doesn’t include special characters ($ and _ are allowed).

There’s an alternative “square bracket notation” that works with any string:

Now everything is fine. Please note that the string inside the brackets is properly quoted (any type of quotes will do).

Square brackets also provide a way to obtain the property name as the result of any expression – as opposed to a literal string – like from a variable as follows:

Here, the variable key may be calculated at run-time or depend on the user input. And then we use it to access the property. That gives us a great deal of flexibility.

For instance:

The dot notation cannot be used in a similar way:

Computed properties

We can use square brackets in an object literal, when creating an object. That’s called computed properties.

For instance:

The meaning of a computed property is simple: [fruit] means that the property name should be taken from fruit.

So, if a visitor enters 'apple', bag will become {apple: 5}.

Essentially, that works the same as:

…But looks nicer.

We can use more complex expressions inside square brackets:

Square brackets are much more powerful than the dot notation. They allow any property names and variables. But they are also more cumbersome to write.

So most of the time, when property names are known and simple, the dot is used. And if we need something more complex, then we switch to square brackets.

Property value shorthand

In real code we often use existing variables as values for property names.

For instance:

In the example above, properties have the same names as variables. The use-case of making a property from a variable is so common, that there’s a special property value shorthand to make it shorter.

Instead of name:name we can just write name, like this:

We can use both normal properties and shorthands in the same object:

Property names limitations

As we already know, a variable cannot have a name equal to one of language-reserved words like “for”, “let”, “return” etc.

But for an object property, there’s no such restriction:

In short, there are no limitations on property names. They can be any strings or symbols (a special type for identifiers, to be covered later).

Other types are automatically converted to strings.

For instance, a number 0 becomes a string '0' when used as a property key:

There’s a minor gotcha with a special property named __proto__. We can’t set it to a non-object value:

As we see from the code, the assignment to a primitive 5 is ignored.

We’ll cover the special nature of __proto__ in subsequent chapters, and suggest the ways to fix such behavior.

Property existence test, “in” operator

A notable feature of objects in JavaScript, compared to many other languages, is that it’s possible to access any property. There will be no error if the property doesn’t exist!

Reading a non-existing property just returns undefined. So we can easily test whether the property exists:

There’s also a special operator 'in' for that.

The syntax is:

For instance:

Please note that on the left side of in there must be a property name. That’s usually a quoted string.

If we omit quotes, that means a variable, it should contain the actual name to be tested. For instance:

Why does the in operator exist? Isn’t it enough to compare against undefined?

Well, most of the time the comparison with undefined works fine. But there’s a special case when it fails, but 'in' works correctly.

It’s when an object property exists, but stores undefined:

In the code above, the property obj.test technically exists. So the in operator works right.

Situations like this happen very rarely, because undefined should not be explicitly assigned. We mostly use null for “unknown” or “empty” values. So the in operator is an exotic guest in the code.

The “for…in” loop

To walk over all keys of an object, there exists a special form of the loop: for..in. This is a completely different thing from the for(;;) construct that we studied before.

The syntax:

For instance, let’s output all properties of user:

Note that all “for” constructs allow us to declare the looping variable inside the loop, like let key here.

Also, we could use another variable name here instead of key. For instance, 'for (let prop in obj)' is also widely used.

Ordered like an object

Are objects ordered? In other words, if we loop over an object, do we get all properties in the same order they were added? Can we rely on this?

The short answer is: “ordered in a special fashion”: integer properties are sorted, others appear in creation order. The details follow.

As an example, let’s consider an object with the phone codes:

The object may be used to suggest a list of options to the user. If we’re making a site mainly for German audience then we probably want 49 to be the first.

But if we run the code, we see a totally different picture:

- USA (1) goes first

- then Switzerland (41) and so on.

The phone codes go in the ascending sorted order, because they are integers. So we see 1, 41, 44, 49.

The “integer property” term here means a string that can be converted to-and-from an integer without a change.

So, “49” is an integer property name, because when it’s transformed to an integer number and back, it’s still the same. But “+49” and “1.2” are not:

…On the other hand, if the keys are non-integer, then they are listed in the creation order, for instance:

:filters:format(jpeg)/f/51376/3358x1684/6c40539c66/foo-bar-example-interface-in-storyblok.jpg)

So, to fix the issue with the phone codes, we can “cheat” by making the codes non-integer. Adding a plus '+' sign before each code is enough.

Like this:

Now it works as intended.

Summary

Objects are associative arrays with several special features.

They store properties (key-value pairs), where:

- Property keys must be strings or symbols (usually strings).

- Values can be of any type.

To access a property, we can use:

- The dot notation:

obj.property. - Square brackets notation

obj['property']. Square brackets allow to take the key from a variable, likeobj[varWithKey].

Additional operators:

- To delete a property:

delete obj.prop. - To check if a property with the given key exists:

'key' in obj. - To iterate over an object:

for (let key in obj)loop.

What we’ve studied in this chapter is called a “plain object”, or just Object.

There are many other kinds of objects in JavaScript:

Arrayto store ordered data collections,Dateto store the information about the date and time,Errorto store the information about an error.- …And so on.

They have their special features that we’ll study later. Sometimes people say something like “Array type” or “Date type”, but formally they are not types of their own, but belong to a single “object” data type. And they extend it in various ways.

Objects in JavaScript are very powerful. Here we’ve just scratched the surface of a topic that is really huge. We’ll be closely working with objects and learning more about them in further parts of the tutorial.

This is by far the most simple tutorial I will be writing. What forced me to write this guide on creating JavaScript key value array pairs, were some comments I received in other Js tutorials.

If you are a Js developer, you might need these scripts probably most of the time. Be it a Js newbie or experienced developer, you will need this guide at some or the other points of life.

Approach :

This post will show multiple ways to define key value array. Choose one that suits you the best, based on the use case.

To give examples, we will be creating an array of students. We will push some student details in it using javascript array push.

We will verify these changes by looping over the array again and printing the result. Basically we will use javascript array get key value pair method.

1. Using an empty JavaScript key value array

var students =[];

students.push({id:120,name:‘Kshitij’,age:20});

students.push({id:130,name:‘Rajat’,age:31});

for(i=;i<students.length;i++){

console.log(“ID:- “+students[i].id +” Name:- “+students[i].name +” Age:- “+students[i].age);

}

Also read: Best JavaScript Frameworks trending now2. Using Javascript Object

In JavaScript, Objects are most important data types. They are widely used in modern Javascript to copy data also.

Objects are different from primitive data-types ( Number, String, Boolean, null, undefined, and symbol ).

Javascript Object Dynamic Key List

This method shows how to combine two different arrays into one array of key-value maps.

Please note that here the assumption is that key-value pairs lie at the same indexes in both existing arrays.

Also read: 5 Best IDE for React and ReactJs text editors3. Using Javascript Maps

Map in javascript is a collection of key-value pairs. It can hold both the object or primitive type of key-values. It returns the key, value pair in the same order as inserted.

Javascript Object Dynamic Key Value

Comment below and let me know if the guide helped you.